Groucho's Cigar, and me.

At some point we’ve all owned something we’ve loved but lost.

We’ve all heard the stories of parents throwing things away when their kids go to college. I had a friend whose Mom threw out a huge stack of Filmore Posters because she couldn’t read the typography on them. Things sold at yard sales that should have handed down to grandchildren.

I’ve had arty and unusual chachkas come and go, but there is one thing I really wish I still had. Something that I can never find on the webbernet, no matter how many searches I do.

I spent a good portion of my childhood in the hospital. Back in the dark ages of television with limited channels and rabbit ears, there wasn’t much daytime variety. The networks, channels 2,4, and 7, had soap operas on all day. Channel 11 showed a variety of old movies, most frequent of which was “Jason and the Argonauts,” a really horrible herky-jerky stop action/live action combo movie. I don’t remember much except there was a cyclops and lots of spears thrown.

Channel 9 had old movies but they also had the New York Mets. The Mets always played daytime games. So there I was, a repeat offender on the pediatric ward of New Rochelle Hospital, watching the worst team in baseball loose game after game. How could I not become a fan?

There was one other bright spot in my “hospital blue” hospital room experience—The Marx Brothers. Channel 9 had most of the Marx Brother catalog and played them in a pretty continuous rotation every few weeks. Each Sunday when the weekly TV listings came out, I would scan the schedule looking for “The Coconuts,” “Duck Soup,” “Monkey Business,” “A Day at the Races,” and “A Night at the Opera.” I would even watch “Love Happy,” though it sort of sucked. It did have a young Marilyn Monroe wooing Groucho.

Lying in my hospital bed I realized there were two kinds of kids. Well, boy-kids more specifically. You had your smack each other in the back of head, whack each other in the face, Three Stooges kids, versus your more nuanced Marx Brothers kids who enjoyed the humor of words over a poke in the eye. I leaned toward sarcasm over violence. I admit it. The Three Stooges were beneath me. All that slapping and nose pulling was just not my style. Even today, not a fan of the nose pulling.

Though often alone in a hospital room I was not alone in my adoration of the Marx Brothers. My friend Stuart was also a huge fan. We could recite lines from each of their movies flawlessly.

“Viaduct?”

“I don’t know why a duck. Why a no chicken?”

“One day I shot an elephant in my pajamas. What he was doing in my pajamas I’ll never know.”

“I never forget a face, but in your case I'll be glad to make an exception.”

Stuart was big, and though he could hit a home run a long way, he wasn’t what you would call athletic. I was pretty uncoordinated even when I could walk, so Saturday showings of the Marx Brothers suited us just fine.

Between us we had Marx Brothers books, posters and albums, but by the time we were full fledged fanatics Groucho was fading. His old TV show, “You Bet Your Life,” was off the air, and other than a guest spot on Cavett or Carson, he was old news. That was until May 6th, 1972.

On May 3rd, my oldest brother Doug arrived from Cornell for some unknown reason. My dad was always suspicious about Doug’s behavior because of his long hair. It was 1972 after all. I’m sure my dad suspected Doug was home for some nefarious drug deal. I don't think my brother even smoked pot but that reality didn’t stop Dad from his belief that Doug was a druggie because he was a college student and all college students were hippies and smoked pot. Once Dad got all freaked out because he smelled something odd that turned out to be oil Doug used to polish his guitar. My Dad was convinced that any smell he didn’t know was pot. My Dad, what a card. Lucky for me, Doug was back for better reasons.

I had just been released from the hospital. On crutches, I’m quite sure I was hating life as I often did back then. It was pretty much a full time thing for me back then to hate life.

So Doug comes back from Ithaca and says he planned a special “get out of the hospital celebration.” This normally involved some sort of cake or new toy, but he walked over and handed me an envelop with “Ticketmaster” printed on the side.

Remember in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” when the hero gets the bar with the golden ticket? Well now imagine I’m Charlie and Doug is Willy Wonka and he has just handed me the bar with the golden ticket. My other brother, Richard, who didn’t like Groucho, he can be an Oompa-Loompa. But that is another story altogether.

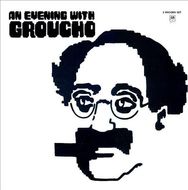

I opened the envelop and there they were—tickets for “An Evening with Groucho,” 12th row, Carney Hall. The tickets were yellow and adorned with a blocky illustration of Groucho. You’ve heard that joke, “How do you get to Carney Hall?” “Practice!” Well, practice is for suckers. I got there by being really sick and having a big brother willing to stand in line at Ticketmaster for a show that sold out almost immediately. A show that I didn’t even know was happening.

The next three days seemed to take a month to pass. I couldn’t wait. We drove into the city, parked the car and walked over to Carney Hall. There was a big crowd, lots of people dressed as Groucho. Some men, and few women, in long tails and greased on mustaches. It was my first big New York event and the first time I had seen adults dressed up in costumes. Pre “Star Trek” people just didn’t do that sort of thing. It was also my first time at Carney Hall and the first time I remember seeing celebrities in person. I got Paul Simon’s autograph and we landed up with seats two rows behind the evening’s host, Dick Cavett.

The show started with a Marvin Hamlish medley of songs we all knew from the movies. With each song everyone got more excited and sang along… “Hooray for Captain Spaulding, the African Explorer. Did someone call me Schnorer? Hooray hooray hooray!’

Cavett did the introductions and did what he always does, talk about when he met Groucho. If you need a professional Groucho talker, Cavett is your man. He did lots of great interviews over the years and I was always amazed at how he managed to insert a Groucho story or imitation in the most unexpected ways. Talking to politicians or actors, musicians or writers, there was always some way for him to slip in a Groucho quip. He was, and is still to this day, a total Groucho name dropper.

Finally, Groucho himself shuffled on stage. He was already in his 80s and he looked frail. I remember thinking he might fall or not be able to make it through the entire show. But there he was, in the winkled flesh sporting a turtleneck, beret and mustache. He looked very Grouchoesque, but not really like Groucho, more like his own grandfather. He crept up to the mic. The closer he got to it, the more energized he seemed. Though his voice was weak he came to life as soon as the spotlight hit him.

He started to sing…

“Hello, I must be going.

I cannot stay,

I came to say

I must be going.

I'm glad I came

but just the same

I must be going.”

After the applause died down he headed to a podium and chair that was waiting for him.

For the next 40 minutes he told jokes and stories of his life, his brother Chico’s womanizing and Harpo’s gambling habits. He sang “Lydia the tattooed lady,” and did a little dance while holding on to the podium.

He spoke slowly, not the Groucho who once shot rapid fire quips in all directions. He took long breaks between stories and it was during one of those long pauses, about 20 minutes into the first half of the show, that he pulled a cigar from his pocket. It was smaller than the ones he smoked in the movies and it was wrapped in plastic. The crappy kind that were sold individually at the corner store. Everyone cheered at the sight of the cigar because really, what is Groucho without a cigar? He’s just Don Rickels. An insult-throwing Jew.

He kept that cigar in his hand for a a couple of minutes as a prop waving it around before finally flicking it across the stage, unopened with his middle finger. Surprised he didn’t smoke it, I thought maybe his doctor had told him to lay off the stogies, but figured he still needed a security cigar, the way a baby needs its blanket.

Groucho walked off stage. The lights come up for Intermission and everyone got up. There was a lot of autograph getting during that break but I would have none of it. I was fixated on that cigar. It was just laying there, on the stage. No one seemed to want it or take notice, and surely after the show it would be swept up by some nameless janitor and tossed away for some rabid NY rat to chomp on. There was only one thing to do. I had to get myself on the l stage and get that cigar.

I looked at all my options. When the lights flickered alerting everyone to head back to their seats, I used the confusion as a cover. I headed forward to the stage. Since I was on crutches everyone made a path for the poor disabled kid. I used the arm supports on the crutches to push myself up onto the stage. I was sure security would come and tell me to get down, but they didn’t. The cigar was still a few feet away, so I used one of the crutches to pull it toward me. It was a small White Owl. I remember thinking, “pretty cheap cigar for Groucho.” I expected a Cuban.

Hamlisch started playing again at the end of the intermission just as I lowered myself down from the stage and swung my body through my crutches back to my seat. No one seemed to have noticed what I had done. No even my brother. I was in heaven. I had Groucho’s cigar. I would never have a way to prove it, but I knew it and if Stuart believed it, that would be good enough.

The second half of the show was one big emotional blur. I was so excited about the cigar. I put it in my jacket pocked and checked it about every 20 seconds because I really couldn’t believe that I had it.

It was the only time Groucho played Carney Hall. It was historic and I had the BEST souvenir. Everyone else had ticket stubs and playbills. I had his cigar.

When we got home I put the cigar on my shelf where it remained until I went to college. Occasionally I would hold it in the same position that Groucho had when he tossed it away. I’d put my middle finger in the bend where he flicked it away and think, “How cool is this!?”

Before I left for college in Arizona, I put it in a mason jar and screwed the lid on tight. It was safe and sound and protected from the elements. During my sophomore year I got the news that my parents had sold the house and all my possessions were being moved to some storage facility in Bronxville. On my next trip back East I grabbed the mason jar/cigar and kept it with me for the next 14 years.

I had moved to San Diego, where the jar rested first on cinderblock shelves, then on thrift store shelves, until I could afford something more adult. When I moved back to NYC, the cigar occupied a prominent place in a beautiful art deco cabinet I found at an auction. All was good with me and the cigar, until my relationship ended and I left Williamsburg.

After the break up I only took a few things. Clothing, my easel, photos albums and that cigar. Nothing else seemed worth discussing or of value. I still liked my ex and I didn’t want to be one of those couples that splits up and fights about every single CD, so I left everything else.

The night before I moved back to California I put the cigar with a few other items back into the family storage space. In the morning I flew to LA to start life over.

It was a few year before I felt settled in Los Angeles. I just couldn’t step foot back in New York City. It had been a low point of my life and everywhere reminded me of how it felt to have an entire city kick your ass. Sinatra said it: “If you can make it here…” well, I couldn’t. I had been defeated.

I think it was around my twentieth high school reunion that I finally felt ready to go back to New York and search through the family remnants that were piled up in that storage space and claim my beloved cigar, only to find that my brother, Richard, had tossed out all the things that he deemed unimportant, to make room for the master audio tapes of his first two albums.

I can’t say I was surprised because, well, Richard, but here I am thinking about it TODAY, because it was Groucho’s cigar, for heaven’s sake. My brother knew what it was, and how the hell do you throw out Groucho’s cigar? I mean, Groucho’s cigar!

That cigar haunts me. It was such a great yet worthless thing, except to me. I’ve lost a lot of other things since then. Most had a lot more monetary value, but they never touched Groucho in significance.

When I think back on that night and the cigar, it only seems fitting to quote Groucho directly: “I've had a perfectly wonderful evening. But this wasn't it.” But it was.